L’articolo è stato aggiunto alla lista dei desideri

Theresa Raquin

Cliccando su “Conferma” dichiari che il contenuto da te inserito è conforme alle Condizioni Generali d’Uso del Sito ed alle Linee Guida sui Contenuti Vietati. Puoi rileggere e modificare e successivamente confermare il tuo contenuto. Tra poche ore lo troverai online (in caso contrario verifica la conformità del contenuto alle policy del Sito).

Grazie per la tua recensione!

Tra poche ore la vedrai online (in caso contrario verifica la conformità del testo alle nostre linee guida). Dopo la pubblicazione per te +4 punti

Tutti i formati ed edizioni

Promo attive (0)

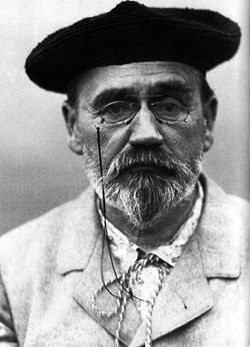

This volume, "Therese Raquin," was Zola's third book, but it was the one that first gave him notoriety, and made him somebody, as the saying goes.While still a clerk at Hachette's at eight pounds a month, engaged in checking and perusing advertisements and press notices, he had already in 1864 published the first series of "Les Contes a Ninon"a reprint of short stories contributed to various publications; and, in the following year, had brought out "La Confession de Claude." Both these books were issued by Lacroix, a famous go-ahead publisher and bookseller in those days, whose place of business stood at one of the corners of the Rue Vivienne and the Boulevard Montmartre, and who, as Lacroix, Verboeckhoven et Cie., ended in bankruptcy in the early seventies."La Confession de Claude" met with poor appreciation from the general public, although it attracted the attention of the Public Prosecutor, who sent down to Hachette's to make a few inquiries about the author, but went no further. When, however, M. Barbey d'Aurevilly, in a critical weekly paper called the "Nain Jaune," spitefully alluded to this rather daring novel as "Hachette's little book," one of the members of the firm sent for M. Zola, and addressed him thus:"Look here, M. Zola, you are earning eight pounds a month with us, which is ridiculous for a man of your talent. Why don't you go into literature altogether? It will bring you wealth and glory."Zola had no choice but to take this broad hint, and send in his resignation, which was at once accepted. The Hachettes did not require the services of writers of risky, or, for that matter, any other novels, as clerks; and, besides, as Zola has told us himself, in an interview with my old friend and employer,[*] the late M. Fernand Xau, Editor of the Paris "Journal," they thought "La Confession de Claude" a trifle stiff, and objected to their clerks writing books in time which they considered theirs, as they paid for it. * * *One Thursday, Camille, on returning from his office, brought with him a great fellow with square shoulders, whom he pushed in a familiar manner into the shop."Mother," he said to Madame Raquin, pointing to the newcomer, "do you recognise this gentleman?"The old mercer looked at the strapping blade, seeking among her recollections and finding nothing, while Therese placidly observed the scene."What!" resumed Camille, "you don't recognise Laurent, little Laurent, the son of daddy Laurent who owns those beautiful fields of corn out Jeufosse way. Don't you remember? I went to school with him; he came to fetch me of a morning on leaving the house of his uncle, who was our neighbour, and you used to give him slices of bread and jam."All at once Madame Raquin recollected little Laurent, whom she found very much grown. It was quite ten years since she had seen him. She now did her best to make him forget her lapse of memory in greeting him, by recalling a thousand little incidents of the past, and by adopting a wheedling manner towards him that was quite maternal. Laurent had seated himself. With a peaceful smile on his lips, he replied to the questions addressed to him in a clear voice, casting calm and easy glances around him."Just imagine," said Camille, "this joker has been employed at the Orleans-Railway-Station for eighteen months, and it was only to-night that we met and recognised one anotherthe administration is so vast, so important!"As the young man made this remark, he opened his eyes wider, and pinched his lips, proud to be a humble wheel in such a large machine. Shaking his head, he continued:"Oh! but he is in a good position. He has studied. He already earns 1,500 francs a year. His father sent him to college. He had read for the bar, and learnt painting. That is so, is it not, Laurent? You'll dine with us?""I am quite willing," boldly replied the other.He got rid of his hat and made himself comfortable in the shop..

L'articolo è stato aggiunto al carrello

Formato:

Gli eBook venduti da Feltrinelli.it sono in formato ePub e possono essere protetti da Adobe DRM. In caso di download di un file protetto da DRM si otterrà un file in formato .acs, (Adobe Content Server Message), che dovrà essere aperto tramite Adobe Digital Editions e autorizzato tramite un account Adobe, prima di poter essere letto su pc o trasferito su dispositivi compatibili.

Cloud:

Gli eBook venduti da Feltrinelli.it sono sincronizzati automaticamente su tutti i client di lettura Kobo successivamente all’acquisto. Grazie al Cloud Kobo i progressi di lettura, le note, le evidenziazioni vengono salvati e sincronizzati automaticamente su tutti i dispositivi e le APP di lettura Kobo utilizzati per la lettura.

Clicca qui per sapere come scaricare gli ebook utilizzando un pc con sistema operativo Windows

L’articolo è stato aggiunto alla lista dei desideri